This week’s blog post includes a linked audio file. Just click on the link below if you would like to hear the post read aloud. Scroll down to read the text.

Our guest blogger this week is Shakina Rajendram, a teacher educator and researcher at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), University of Toronto. Shakina’s research focuses on preparing teachers to support plurilingual learners in K-12 classrooms through multiliteracies, collaborative learning, and translanguaging.

“Good morning, students. My name is Shakina, and I’m here to learn Tamil from you.” 35 faces stared back at me, with looks of confusion and slight amusement in their eyes. A few students stole quick glances at the daily schedule plastered on a notice board at the back of the classroom. It was their English period now, and they were expecting to meet their new English teacher for the year. So, who was this person at the front of the classroom asking to learn Tamil from them, then? A few students muttered something to each other under their breaths. I continued, “I’m brand new to your school, and my Tamil isn’t very good. I heard that you’re all Tamil language experts, and I would love for you to be my teachers this year.” A few students chuckled quietly, but still, no one responded to me. I gathered up all the courage in me and said something in the little Tamil I knew, “நான் தமிழ் கொஞ்சம் கொஞ்சம் தெரியும்” (I know Tamil, a little little). Laughter erupted all across the room. “Teacher, எப்படி இல்லை!” (Teacher, that’s not how you say it!). I smiled. This was going to be the start of a beautiful plurilingual journey together.

In 2010, I was commissioned by the Malaysian Ministry of Education to teach English in a Tamil-medium primary school in the state of Selangor in Malaysia. As I had received a full scholarship from the Malaysian government to pursue my Bachelor of Education in the United Kingdom, I was contracted to teach English in any public school of their choosing for at least 4 years after I graduated. I was posted to a primary school in the minority Malaysian-Indian community. Tamil was the official medium of instruction for most subjects in this school, and English was taught as a separate subject. The night I received my offer letter and found out where I would be teaching for the next 4 years, I was awake all night, my mind racing with many anxious thoughts. Although I was a Malaysian-born Indian myself and had learned Tamil for over 10 years, I did not consider myself to be a proficient speaker of Tamil. I was afraid that I would be perceived as an outsider in this community because of my lack of proficiency in the language. I was anxious about not being able to communicate and connect with my students and their parents. I was embarrassed about having an “accent” when I spoke in Tamil, about the countless pauses and fillers in my speech. I was worried I would not know how to express my thoughts clearly when speaking in Tamil.

It was only after I spent some time getting to know the students in my school that a very important realization dawned on me – a realization that would go on to determine the course of my teaching and research. How I felt about Tamil was exactly how many of my own students felt about English, except that the stakes were much higher for them, and they had experienced a systemic marginalization of Tamil that I had not experienced with English. Although I, too, was a member of the minority Indian community in Malaysia, I had grown up speaking in English as my home language from a very early age. My proficiency in the language had opened up many educational and career opportunities for me, both in Malaysia and beyond. But for these students who spoke Tamil as their home language, even seemingly simple tasks like introducing themselves in class could be very daunting because they usually had to do it all in English, or not at all.

In my first few days in school, I quickly observed that most of the English teachers there had an English-only policy in place in their classrooms, and did not allow their students to use Tamil. This came as no surprise to me. Having done my entire primary and secondary schooling in Malaysia, I understood how educational policy changes over the years had put immense pressure on English teachers to teach monolingually. For example, in 2003, the English for Teaching Mathematics and Science (ETeMS) policy which changed the official medium of instruction for Mathematics and Science to English required all Mathematics and Science teachers to start teaching their subjects only in English. This placed a very high expectation on English teachers to improve the English language proficiency of their students to assist them with learning Mathematics and Science content in English (Rashid, Abdul Rahman, Yunus, 2016). In 2012, as part of the Upholding the Malay Language and Strengthening Command of English (MBMMBI) policy, all English teachers were required to achieve a C1 or C2 in the Cambridge Placement Test (CPT) as part of the Ministry of Education’s aim to “stick to Britain’s standards of teaching the language in order to enhance the quality of teaching English in Malaysia” (Rajaendram, 2015).

The belief that “Britain’s standards” should serve as the benchmark for English proficiency has its roots in Malaysia’s colonial history. During British colonial rule in Malaysia, the hegemony of the colonizing state was maintained through raciolinguistic ideologies (Rosa & Flores, 2017) which positioned English as superior to racialized local languages. English served as the language of government, commerce, education, and the media, and proficiency in English symbolized socioeconomic mobility, power and prestige (Low & Ao, 2018). Post-independence, although Malay was chosen as the new official language and Tamil and Chinese were used as mediums of instruction in schools for the Malaysian Indian and Chinese communities, English continues to be the pathway to many higher education and employment opportunities in the country. Thus, the ‘colonial habitus’ (Rassool, 2007, p. 16) has continued to influence the practices of many well-intentioned teachers who believe that English-only instruction is the best way to ensure educational and socioeconomic progress for their students.

Thus, going into my Grade 3 classroom on my first day as their English teacher, I knew that my students were expecting me to converse with them only in English, and to tell them that they had to do the same. But I had decided to do just the opposite. All the teachers, parents and students I had met in my first few days in the school had been so gracious in affirming and praising my attempts at speaking in Tamil, telling me not to apologize for what I kept referring to as my “broken Tamil,” and assuring me that it was okay if I needed to “mix Tamil and English.” I made a decision there and then that I would never impose English on my students, but instead, seek to learn from and with them. By introducing myself to my students as someone who was there to learn Tamil from them, I was trying to position myself not as their English teacher, but as a fellow language learner. That was the start of a wonderful 4.5-year-long plurilingual learning journey I shared not only with that group of students, but with many other Grade 1-6 classes in that school. In each class I taught, I reminded my students that we were all language learners, and we were there to learn all the languages collectively spoken by the members of our community. Instead of reading passages in the textbook, we read the information on plurilingual signboards in our neighbourhood; instead of writing essays, we composed plurilingual stories and songs and performed them at community events; instead of practising how to pronounce English words “correctly,” we learned and celebrated the different ways that English words were pronounced all over the world. Our lessons looked, sounded, and felt different from many other English classrooms I had been in, because we had created a community of practice through our plurilingual interactions and collaboration. This had a transformative effect on the school learning environment, as parents, teachers and administrators came to embrace a culture of collective language learning.

It was only many years later, when I started my graduate studies at OISE, that I began to understand theoretically what was taking place pedagogically in my classrooms. The key tenets of plurilingualism, translanguaging and sociocultural theory helped me understand that my students and I had created a translanguaging space (Li Wei, 2011) through our collaborative language learning. In this space, my students and I were drawing on our shared knowledge, experiences, and plurilingual repertoires to support each other in a way that expanded our individual and collective learning. I was not the sole source of expertise in our translanguaging space. Rather, expertise was distributed – all my students were empowered to take on the role of language experts because they were able to use all the language practices and features (García & Li Wei, 2014) in their linguistic repertoire.

García and Li Wei (2014) and Li Wei (2014) propose a translanguaging as co-learning approach which draws from Brantmaier’s (n.d.) model of co-learning. This model challenges the unequal power relations in the classroom by changing the respective roles of teachers and learners from “dispensers and receptacles of knowledge” to “joint sojourners” on a journey to acquire knowledge and understanding (Brantmaier, n.d., as cited in Li Wei, 2014, p. 169). In the co-learning model, the teacher takes on the role of a learning facilitator who guides students’ learning process, a scaffolder who assesses what students know and provides scaffolding to extend their knowledge, and a critical reflection enhancer who engages students in reflection on what is being learned and in meta-reflection on the learning process. Meanwhile, the learner takes on the role of an empowered explorer who independently or collaboratively explores knowledge, and a meaning maker and responsible knowledge constructor who constructs meaningful knowledge that is relevant to their life. A teacher does not need to be plurilingual or be able to speak the same languages as their students in order to enact a translanguaging as co-learning approach in the classroom. What is required is the teacher’s “willingness to engage in learning with their students, becoming an equal participant in the educational enterprise that should seek, above all else, to equalize power relations” (Flores & García, 2013, p. 256). In my PhD dissertation, “Translanguaging as an Agentive, Collaborative and Socioculturally Responsive Pedagogy for Multilingual Learners” (Rajendram, 2019), I provide recommendations for a collaborative translanguaging pedagogy based on the translanguaging as co-learning approach.

My current teaching and research both involve preparing teacher candidates in the Master of Teaching program at OISE to support plurilingual language learners in K-12 classrooms in Ontario. These are a few of the ways that I try to cultivate a learner’s stance among my teacher candidates:

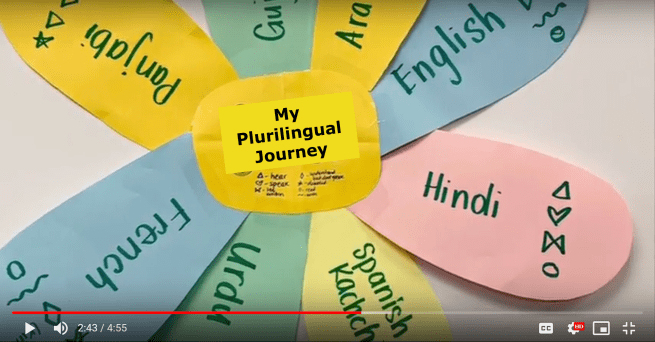

- All my teacher candidates complete a multimodal Plurilingual Journey assignment, where they reflect on the challenges and successes they have had along their language learning journey, talk about the relationship between their language, culture and identity, and think about how their own experiences as plurilingual learners can inform their future teaching practices.

- Throughout the semester, we engage in various identity-focused activities, for example, creating our own I Am From and What Do You See When You Look At Me? poems using apps such as Scribjab, MyStoryBook and Pixton. Throughout the creation of these digital poems, teacher candidates reflect on how they can use identity-focused activities to connect with the language learners in their future classrooms.

- I show students videos of plurilingual children and youth across Ontario (from the Me Mapping with Language Learners project that I’m involved with at OISE), and encourage my teacher candidates to think critically about what they can learn from the wealth of expertise and experience these learners bring with them to the classroom.

- I model to teacher candidates how to intentionally incorporate translanguaging strategies such as multilingual reading and writing groups, multilingual research, multilingual word walls, and cognate charts into their unit and lesson plans across the various subjects they will be teaching.

- During their practicum, I ask my teacher candidates to spend time connecting and interacting with a plurilingual learner, get to know the learner’s life story, identify the learner’s language strengths, and create a plan to support that learner’s plurilingual development based on a translanguaging as co-learning approach.

Through these and other activities, I hope that the teacher candidates I work with come to see themselves, just as I did back in my very first Grade 3 classroom in Malaysia, as joint sojourners and co-learners on a beautiful plurilingual journey with their students.

References

Flores, N., & García, O. (2013), Linguistic third spaces in education: Teachers’ translanguaging across the bilingual continuum. In D. Little, C. Leung, & P. Van Avermaet (Eds.). Managing diversity in education: Key issues and some responses (pp. 243-256). Multilingual Matters.

García, O., & Li Wei. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave MacMillan.

Li Wei. (2011). Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035

Low, E. L., & Ao, R. (2018). The spread of English in ASEAN: Policies and issues. RELC Journal, 49(2), 131-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688218782513

Rajaendram, R. (2015, January 28). Teacher do better in test. The Star Online.

Rajendram, S. (2019). Translanguaging as an agentive, collaborative and socioculturally responsive pedagogy for multilingual learners [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Toronto.

Rashid, R. A., Abdul Rahman, S. B., & Yunus, K. (2016). Reforms in the policy of English language teaching in Malaysia. Policy Futures in Education, 15(1), https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210316679069

Rassool, N. (2007). Global issues in language, education and development: Perspectives from postcolonial countries. Multilingual Matters.